TOPICEXHIBITION2020.08.11

“Why I Work With Artists” –An interview with Hiroshi Hara on the occasion of the Shintaro Tanaka exhibition

Art Front Gallery has collaborated with numerous artists in hopes to make use of art in development projects and living spaces. It is indeed a challenge for both artists and us to create works that an unspecified number of people view and engage with under various conditions as opposed to within museums and galleries, yet we believe that these projects serve to re-question the meaning of art that connects people and places, as well as people and people. One of such artists whom we have worked with over the years is Shintaro Tanaka, who passed away in August last year.

On the occasion of Shintaro Tanaka’s solo exhibition “The Landscape Veers Perpendicularly” (August 8 – October 18, 2020) being held at the Ichihara Lakeside Museum, we spoke with architect Hiroshi Hara who has maintained a close relationship with Tanaka since the 1960s, and asked him to talk about Tanaka’s works and reflect on the 1960s in which they met, and also the reason as to why he works with artists.

――You were born in 1936, and Shintaro Tanaka in 1940. That is to say, you are almost of the same generation. Could you tell us about how you two met one another?

Hara: We first met one another on the occasion of the “From Space to Environment” exhibition in 1966. The art critic Yoshiaki Tono curated the exhibition, and he had selected a number of promising artists to take part, which included the likes of Keiji Usami, Shintaro Tanaka, and myself. Tono enjoyed skin diving so at one time we all went to the island of Hachijo-jima to catch fish. Tono was a truly wonderful person, and it is a great shame that he is no longer with us as he had succeeded in bringing people from various fields together. I wonder if there’s anyone in our generation who had managed to play a role like him.

――The “From Space to Environment” exhibition was a crosscutting venture in art, design, architecture, photography, music, and other creative fields. The 1960s seemed to be a lively and vibrant era in which diverse people met and collaborated with one another.

Hara: Yes, those were indeed vibrant times. However, looking back on Japanese history, the 1200s, when the Heian period was about to end, or had just ended, was an incredible era in which three remarkable figures, Kamo no Chomei (1155-1216), Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) and Dogen (1200-1253) were all alive at the same time. The 60s by no means stands a chance against this era, yet still, the times weren’t so bad. As it is in fact apparent today, by the time we were born, the world was already somewhat organized, and there was a real sense of beginning. The times permeated with a feeling of naiveté and also harbored various possibilities. It was a time in which dialectic thinking and the concept of “Not-not” were at once present. It is to raise a question not under the pretense that there is one correct answer, but rather, was a situation in which two things appeared to overlap with one another. No matter what one does, it may in fact be meaningless. Nevertheless, I think we all firmly believed in one thing, and in doing so, attempted to create a system or narrative. In terms of someone of my generation, Nobel laureate novelist,Kenzaburo Oe is a good example. Ever since his novel A Personal Matter (1964), he has built his very own device and has continued to write while repeating the same pattern. I am truly amazed by his obstinance. I feel that Shintaro Tanaka was also such an artist.

――How was your impression of Shintaro Tanaka?

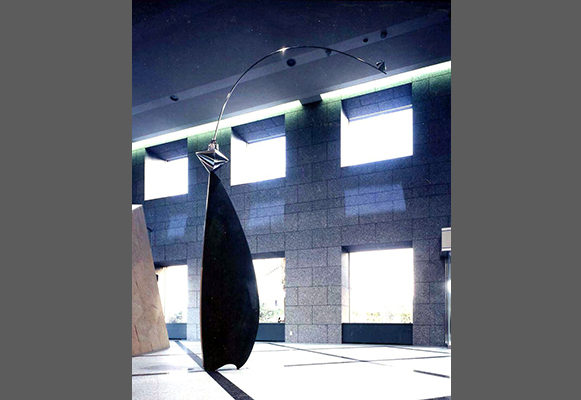

Hara: As you know, Shintaro Tanaka had not attended an art university. In our generation, there were some artists who did not go to university while some artists did. The former include figures such as Toru Takemitsu, Shuntaro Tanikawa, Keiji Usami, and Kiyoshi Awazu. Takemitsu for example, had the air of an artist just by the way he presented and carried himself, which you could sense even when he was simply just standing there. I think Tanaka too was likely this kind of person. He was always standing straight and upright, and I wonder whether he had continued to pursue this sense of uprightness throughout his entire life. God states that it is difficult for humans to stand upright. Buildings are also basically built to stand upright. In architecture the term “vertical” is used, which refers to the direction in which gravity acts, and the basis of architecture is thus to create a means to be free from this gravitational force. Architecture can collapse if it remains unstable, therefore erectness and verticality are at once the fundamental principles and challenges of architecture. Tanaka appeared to create works with a certain sense of instability reminiscent of a balancing toy, yet what he had in essence created were works that maintained both balance and stability through abandoning the anxiety towards the needs for them to be vertical. Despite their seemingly unstable state, they perfectly settle into place. I feel that perhaps the principle of his aesthetic was to maintain a situation in which humans, in the midst of, and because of this very contradiction, were necessitated to stand upright. In 2001 he created a work titled Pianissimo of North Sky in the approach leading up towards Sapporo Dome. It is a remarkable work that takes on the form of a mobile. I am also very fond of his work with the red dragonfly, which he created in the previous year for the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2000.

――Shintaro Tanaka had also engaged in numerous commission works, leaving behind an array of high-quality projects, and also continuing to produce work until the very final years of his life.

Hara: Even if it appears from the outside like someone is repeating the same thing, he/she would lose interest or become indifferent if he/she did not believe in history and have the awareness of sharing history. Humans are existences that can be in doubt and lose their way. An artist is always at odds with his or herself.

――You have worked with artists on numerous occasions. There are many architects that regard their architecture as a complete work in its own right, yet many of the buildings you have designed serve to engage with art. The first case was the Umeda Sky Building (1993), in which Art Front Gallery was also involved. Tanaka’s work is installed in this building as well.

Hara: Yes, it was my idea to incorporate art, but in terms of Umeda, I believe it was also a decision on part of the client Sekisui House. We architects constantly find ourselves to be anxious. What if things fall or collapse due to an earthquake, and end up putting people’s lives at risk? We are always nerve-ridden thinking about these things, as we indeed have a responsibility. That being said, when we form a team so that the responsibility doesn’t fall on the individual, we tend to become overconfident. Artists aren’t as nervous and don’t live in fear and anxiety, yet they take on all responsibility on their own. They may of course work as a team from time to time, yet they stand as individuals. Ultimately, it is the actions of each individual that come to surface within history. Artists are people who firmly hold their ground. That’s why we get along with each other. Architects perceive and understand the world in a superficial way. They are arrogant, while they should be humble. Architects don’t understand that there are people in the world of art, science, mathematics et al that are so remarkable, that they are beyond comparable to themselves. The fact that there were the three great masters of the 1200s, as well as the sheer tension of the 1960s when great figures like Sartre and Camus were alive. The works of Christo, who passed away recently, were easy to comprehend, yet had reflected his highly acute and computational mindset. Joseph Kosuth is also very intelligent. Tanaka’s practice is easy to comprehend as well. I feel that he continued to produce work by repeatedly suppressing his sensibility under the pretense that magnets and balancing toys were all that existed in the world, and further believing in this principle. This is essentially what is so remarkable about his practice.

Please also visit “Shintaro Tanaka’s exhibition” at Art Front Gallery in Daikanyama. 2020. Sep. 11 (Fri) – Oct. 11 (Sun)

Note: The exhibition “From Space to Environment” was held from November 11th to 16th, 1966 on the 8th floor of Matsuya Department Store in Tokyo’s Ginza District. It featured 38 individuals from fields of art, design, architecture, photography, and music, and is said to have had 35,000 visitors in just six days.

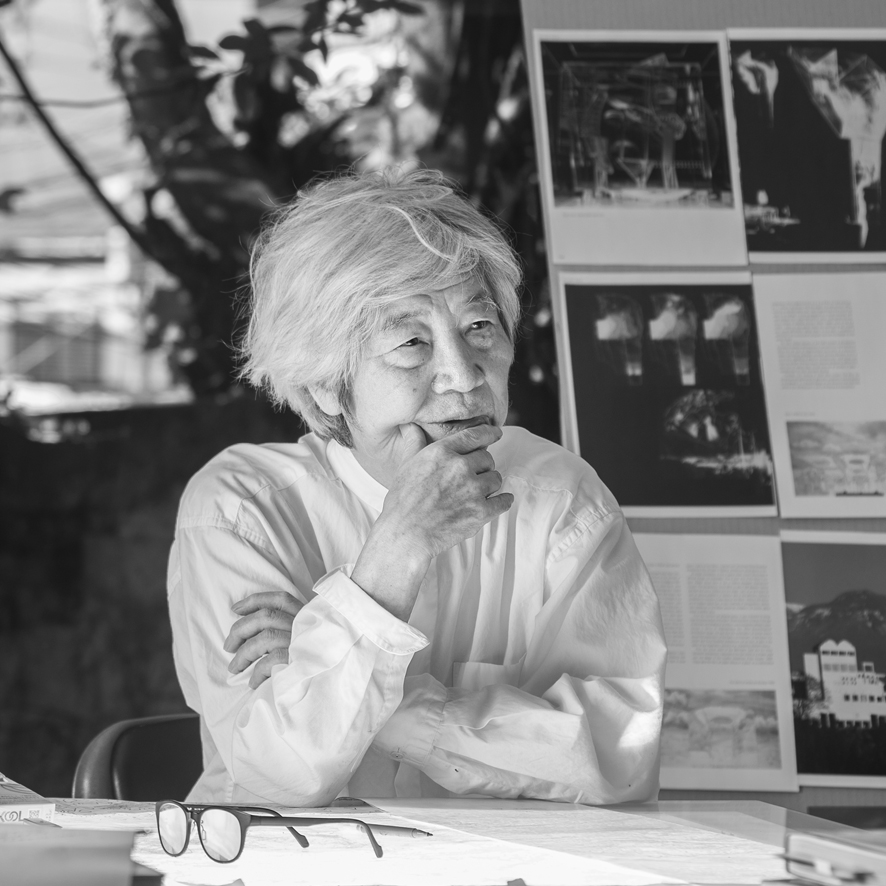

Hiroshi Hara : Architect and Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo.Born in 1936 in Kawasaki, Japan. He collaborated with Atelier Φ Architects from 1970 to 1998, and He changed the designation to “Hiroshi Hara + Atelier Φ” from 1999. Professor Ad Honorem, National University of Uruguay (2001).His major works include “Tasaki Museum of Art”, “Yamato International”,”JR Kyoto Station”, “Uchiko Town’s Ose Junior High School”, and “Sapporo Dome”. He is the author of What Is Possible in Architecture (1967), Space (from Function to Aspect) (1987), Journey to the Village (1987), and DISCRETE CITY (2004).

translated by Kei Benger

UPCOMING

TOPIC

4/23(火) 北川フラム塾 第30回 地方芸術祭と震災-奥能登を中心に(ゲスト:暮沢剛巳)

Exhibition

Oscar Oiwa solo exhibition:Oil Octopus in the era of turbulent at Shibuya Hikarie 8/,Apr.27-May.12

TOPIC

Uchiboso Art Festival will be held from March 23rd.

TOPIC

The Oku-Noto-Suzu Yassar Project has been launched.

TOPIC

Art Festivals and Exhibitions 2024